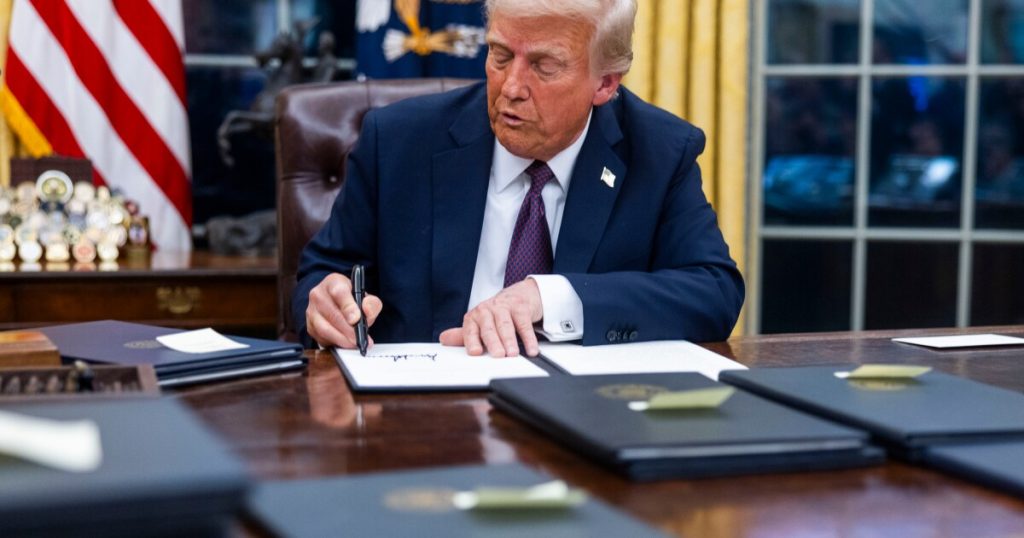

During his first days in office, President Donald Trump has shown a willingness to test the limitations of what can be done by executive action. What remains to be seen is whether he takes a similar tack for bank regulation.

Trump signed 48 executive orders, proclamations and memoranda within roughly 24 hours of his inauguration. These actions touched policies related to the military, trade, energy,

Financial regulation is rarely a “

Still, Trump’s initial flurry of actions could be a sign of things to come, for the banking agencies and the administrative state writ large. Trump signed 220 orders during his first term, and Alt anticipates a greater reliance on direct action this time around.

“The notable difference thus far is there has been less open resistance to Donald Trump,” Alt said. “There is a very unified Republican Party and a Supreme Court that has been noticeably deferential on several matters regarding President Trump. We’re not seeing the kneejerk response of ‘Gosh, he can’t do that.’ We’ll have to wait and see, but I expect he will use executive orders to effectuate his policy goals quickly.”

Presidential directives can be powerful tools of governance, but they can also occupy something of a legal gray area. In some cases, they can change government practices immediately. In others, they serve more as guideposts for what the administration wants its agencies to do — or stop doing.

A cornerstone of Trump’s political agenda has been easing regulatory burdens across all sectors. The

Austin Evers, a partner at the law firm Freshfields Brukhaus Deringer and a former associate deputy attorney general with the Justice Department, said Trump’s preferences for bank policy could eventually be spelled out through executive action, but the president cannot change regulations with the stroke of the pen. Because legislation takes precedence over executive action, agency rule changes remain subject to the stipulations of the Administrative Procedure Act.

“An executive order has the force of law within the executive branch, but if one of the next steps is to rescind regulations or to adopt new regulations, that process has to go through the formal notice-and-comment rulemaking process,” Evers said. “Deregulation is by definition regulation, and that’s going to take time.”

Executive orders can speed up certain policy implementations, but they can also be undone fairly easily by Congress, the courts or future presidents. Indeed, during his initial blitz of orders, Trump undid nearly 80 directives from his predecessor, President Joe Biden.

Trump’s end to birthright citizenship — which deals with the interpretation of the 14th Amendment — could prove to be a litmus test for his ability to singlehandedly upset long-running norms. But other actions appear to be safely within the president’s remit. This includes his call for a freeze on all new and pending regulations. This is a standard procedure when a new president comes into power, but among the first wave of orders, it appears to have the most direct impact on the banking sector.

Evers said other orders, including Trump’s reversal of the

“Executive orders on certain topics are going to impact the banking industry,” he said. “Among the orders that Trump rescinded was President Biden’s executive order on AI, and that will have implications across the federal bureaucracy, and knock-on effects for the sectors that are regulated by that bureaucracy.”

There is a debate, however, about the degree to which bank regulators — namely the Federal Reserve and Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. — are required to follow executive orders. As independent agencies, they are not directly accountable to any specific executive department. The OCC, by contrast, is a bureau of the Treasury Department and subject to executive orders more directly.

Alexandra Steinberg Barrage, a partner with the law firm Troutman Pepper Locke and a former FDIC executive, said the agencies traditionally have sought to adhere to the “spirit” of executive actions, whether they be bank policy priorities or calls to reduce staffing.

“They are not executive agencies, but at the same time they’ve acted, in my experience, in accordance with those directives,” Barrage said.

Barrage also noted that presidents can steer bank policy through their appointments of agency principles. Because of this, she said, presidents have been able to rely on less-binding forms of guidance, such as industry reports and fact sheets to signal regulatory preferences.

Still, recent history has shown that the banking agencies are not always in lockstep with one another or the White House. Barrage pointed to a Biden-era directive on competition, which called for new standards on bank merger reviews. The OCC finalized a new rule on merger oversight, while the FDIC merely updated its policy statement and the Fed took no action at all.

Similarly, she said, the Fed has refrained from updating its policies on clawing back compensation from executives who mismanage banks, something called for by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010.

Barrage said it remains to be seen how much freedom Trump will give the banking agencies to set their own agendas.

“Who’s driving the policy on banking? That’s really the question,” she said. “Are we going to see more actions from the agencies themselves, based on industry comments and statements on the Hill? Or are we going to see reform guided by specific executive direction?”