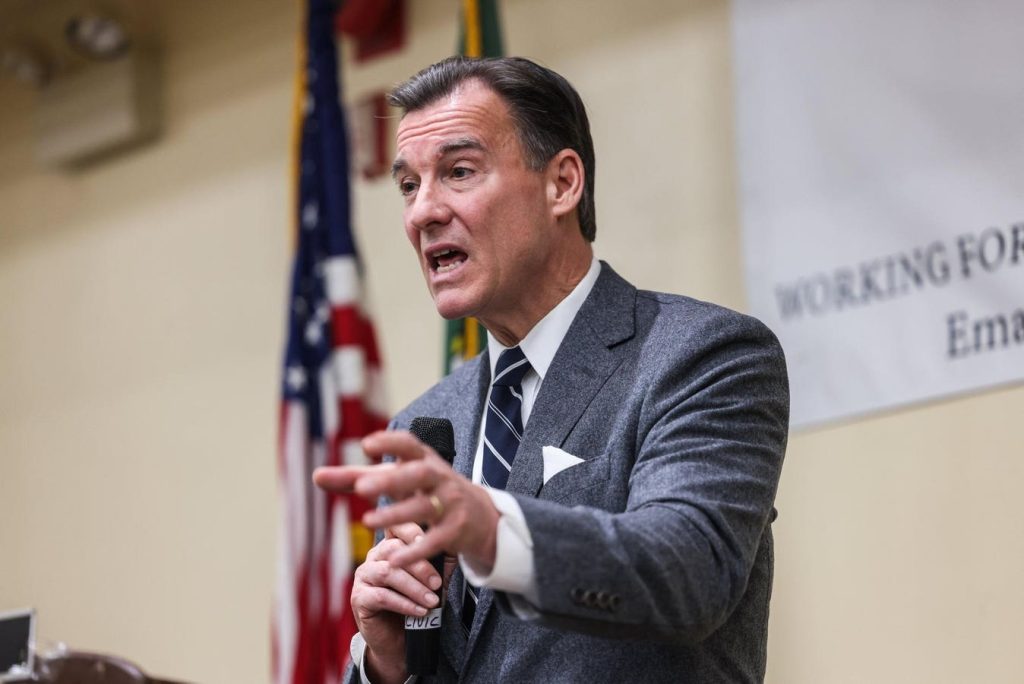

New Hyde Park, N.Y.: Tom Suozzi, running in a special election for New York’s 3rd Congressional … [+]

Later this year, Rep. Tom Suozzi (D-NY) will reintroduce his public catastrophic long-term care insurance bill, called the WISH Act. Suozzi is doing all the right things: Looking for Republican support and trying to engage the private insurance industry, long-term care providers, and employers, as well as advocates for older adults and people with disabilities.

But he has a big problem: While the idea of public insurance may be gaining traction, raising taxes to pay for it is a much tougher sell.

Suozzi’s original 2023 bill explicitly proposed raising payroll taxes to fund the insurance program, an idea consistent with the levy used by most other developed countries. But his 2025 version may leave out a specific tax and try to first build support for the insurance idea, then deal with thorny funding problem later.

Universal And Fully Funded

That may make good political sense but it won’t change the twin realities of a public insurance program. It must be mandatory. And if it is to be self-sustaining, as it should be, it must be accompanied by some kind of tax increase.

Public insurance must be mandatory (or universal, if you prefer) because if people can choose to participate, they won’t enroll until they think they need coverage. And if only those who need it buy it, premiums inevitably will rise to levels where insurance is unaffordable. And the system collapses.

That happened in 2010, when Congress passed a voluntary public program called the CLASS Act. Once the actuaries realized how high the premiums would be, the Obama Administration abandoned the idea.

And if a public program is going to pay for itself, it must be accompanied by a tax. You can call it a premium or a contribution, as they do in Europe. But lawmakers will need to adopt some form of tax to fund the insurance.

A Modest Tax

The levy would be modest. In 2016, the Long-term Care Financing Collaborative, which I helped create, proposed a public catastrophic plan that could be self-funded with a payroll tax of about 0.6 percent. Washington State enacted a different insurance model called WA Cares that will cover the first $36,500 of costs, adjusted for inflation, for roughly the same size payroll tax.

How much is 0.6 percent of payroll? A median income full-time worker who makes $60,000 annually would pay $360-a-year in additional taxes, or about $7 a week—roughly the cost of a Happy Meal. In either plan, they’d need to pay the tax for at least 10 years to qualify for benefits.

For context, in 2023, a single male aged 55 typically paid about $2,100 in premiums for a $165,000 private policy with 3 percent inflation protection, according to the American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance. A similar female buyer paid $3,600.

Keep in mind that as many as one-third of prospective private long-term care insurance buyers are rejected because of pre-existing medical conditions or family history. By contrast, a public program covers everyone, as long as they pay the tax for the required number of years.

Support From Private Insurers

One positive political change since Suozzi first introduced his bill: Some long-term care insurance carriers are embracing the idea of a public catastrophic program. They realize that it could revive their moribund business by creating an opportunity to sell policies that complement a government program. One big player, Genworth, is publicly backing the idea and other carriers are quietly looking at it.

Few if any new private policies cover catastrophic costs. But carriers see an opportunity to fill any coverage hole left by government programs, perhaps even state-run front-end benefits combined with a federal catastrophic plan. Says Lynn White, president and CEO of CareScout, a unit of Genworth, “We’d be fine being sandwiched in the middle.”

Such a model would provide more claims certainty, allowing insurers to offer coverage at more affordable rates. Plus, because such a program would raise consumer awareness of the need for long-term care as well as the limitations of the public benefit, it could help build a market for private insurance.

That’s what happened when retirees bought Medicare Supplement (Medigap) insurance that picks up where traditional Medicare leaves off.

Overcoming GOP Reluctance

But one thing has not changed: Republican lawmakers seem disinclined to support either an unfunded social insurance program or any tax increase that could pay for it.

Yet, such a tax hike may be politically possible. Just this past November, Washington State voters rejected a referendum that would have killed their tax-funded program. Washington is a blue state, but there still may be a lesson here.

Reluctant lawmakers may also come to realize that public insurance could lower Medicaid’s long-term care costs, currently more than $200 billion annually, by as much as one third over time. And older adults and younger people with disabilities would be far better off with an insurance benefit than with Medicaid.

A public long-term care insurance program will be increasingly important as the population ages and the costs of care rise. But it won’t happen without broad support, including from Republicans. And for that to happen, backers are going to have to find a palatable way to pay for it.